COVENTRY, United Kingdom — One of the biggest obstacles physicians face is treating infections that become resistant to antibiotics. As scientists look to beat these adapting germs, one study says the answer may be in the distant past. Researchers find a 1,000-year-old medieval remedy can actually be useful in fighting several types of bacteria, including ones which commonly infects diabetic ulcers.

Researchers at the University of Warwick say “Bald’s eyesalve” mixtures contain onion, garlic, wine, and bile salts. Testing how these ancient remedies affect various germs, the study reveals Bald’s eyesalve is effective against both Gram-negative and Gram-positive wound bacteria.

An ancient cure-all?

Among these dangerous strains is Staphylococcus aureus, a bacteria nearly one third of the population carries in their nose. It’s usually harmless, but it can cause infection and even death when coming into contact with cuts and torn skin.

Bald’s eyesalve also shows promising results against:

- Streptococcus pyogenes: Which causes infections like tonsillitis and scarlet fever

- Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: Commonly linked to respiratory infections

- Acinetobacter baumanii: A common infection seen among combat wounds

- Staphylococcus epidermidis: Which causes infection in patients with catheters, surgical wounds, and those with compromised immune systems

“We have shown that a medieval remedy made from onion, garlic, wine, and bile can kill a range of problematic bacteria grown both planktonically and as biofilms,” Dr. Freya Harrison says in a university release. “Because the mixture did not cause much damage to human cells in the lab, or to mice, we could potentially develop a safe and effective antibacterial treatment from the remedy.”

What makes Bald’s eyesalve work?

Researchers say the use of garlic in Bald’s eyesalve mixes may be a key ingredient. Garlic contains allicin, which produces its famous smell, but also has links to anti-inflammation and immunity health. Although it helps, the British team says allicin alone can’t fight bacteria to the extent they’re seeing. They add this special combination of ingredients gives this 1,000-year-old formula its strength.

“Most antibiotics that we use today are derived from natural compounds, but our work highlights the need to explore not only single compounds but mixtures of natural products for treating biofilm infections,” Harrison explains.

“We think that future discovery of antibiotics from natural products could be enhanced by studying combinations of ingredients, rather than single plants or compounds.”

Finding innovations in medieval medical journals

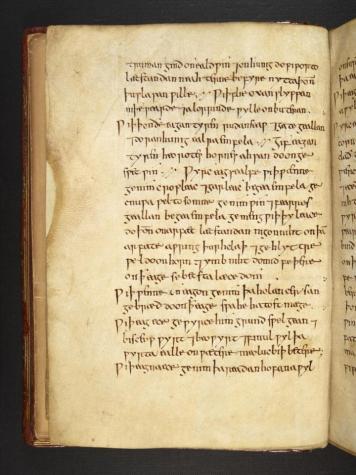

Before this study, co-author Christina Lee of the University of Nottingham read through the Bald’s Leechbook. This book is an Old English leatherbound volume in the British Library and is believed to be one of the oldest medical textbooks containing Anglo-Saxon medical information. Bald’s Leechbook gives advice and recipes to make natural medicines, salves, and treatments during medieval times.

“Bald’s eyesalve underlines the significance of medical treatment throughout the ages,” Lee says. “It shows that people in Early Medieval England had at least some effective remedies.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, antibiotic-resistant bacteria causes infections in 2.8 million people in the United States each year. More than 35,000 of those patients die from these strains.

The study appears in the journal Scientific Reports.